It is one of the greatest works of Roman architecture and Roman (social) engineering.

The new Yankee Stadium under construction.

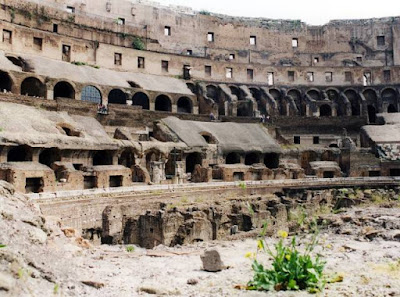

The new Yankee Stadium under construction.Taking a closer look at the Colosseum you realize what a magnificent arena this must have been.

Stand at ground level you can look up at the remains of the most complete side of the structure.

The stands seem so much steeper than modern stadiums, almost vertical, and when full, it must have felt like the crowd would fall on top of you.

It was here that for the first time, sport was widely used as a form of mass entertainment.

The ancient Roman sports may have been very different from the codified spectacles we watch today, but many factors that permeated sport then, still hold true today.

The gladiatorial contests and chariot races that took place were used to occupy the masses, distracting them from what was really happening.

To put on good games was, in a sense, a sign of respect for the people, and a way of winning their trust and affection--a valuable political resource for the future.

As the value of the games as springboards to political success became more and more apparent, competition between public figures to woo the people through spectacle, escalated--leading to ever more lavish and innovative presentations.

This trend delighted many, but also alarmed many. The importance of positions which provided unparalleled opportunities for advancing one’s political career by allowing one to stage the games, led to frequent cases of bribery, as candidates competed fiercely to attain these posts.

The fact that bribery to gain office was a capital offense was only a slight deterrent.

More than this, many clear-thinking Romans came to see the games, themselves, as forms of bribery.

Although the games were, obviously, not considered to be bribery in any strictly legal sense, their impact and use by ambitious politicians could not be discounted by citizens concerned about the future of their democracy.

The growth of the games in Rome was, therefore, not uncontested: philosophers and legislators frequently sought to limit their effect, to prevent them from distorting the political system and from "corrupting the morals of the people."

Moved by these concerns, the government experimented with placing spending caps on the games, as public officials frequently supplemented state funds, with private funds (drawn from their own fortunes, or raised from their political associates), in order to be able to put on ever more spectacular shows.

The clear intent was to prevent individuals from "buying elections" by means of the games.

Along similar lines, there were sometimes efforts to limit the number of gladiators that wealthy sponsors could present. In 65 BC, for example, the massive gladiatorial spectacle that Caesar originally planned was downsized by other politicians.

Although the principal justification was based on security--for the fierce revolt of Spartacus was still on the people’s mind, and the presence of so many well-trained, well-armed gladiator-slaves in the city seemed rather frightening--there was certainly also the motive, brought into play by Caesar’s political opponents, of stunting one avenue by which their rival might gain in political stature.

Interestingly enough, while the gladiatorial games generated some criticism on the basis of their "wasteful extravagance"; their political impact; and the occasional appearance of a free Roman citizen (lowering himself to the level of a criminal or slave in order to obtain glory as a gladiator, at the price of demeaning his class), few humanitarian objections were raised.

Those who lifted their voices against the games on account of their cruelty and brutality appear to have been a rather ineffective minority.

Laws prohibiting Roman nobles of the senatorial and equestrian orders from participating in the games as gladiators, charioteers, and actors were in effect (but they were also frequently violated).

The ruling class feared to present itself on the same level as those it had conquered and enslaved, for these spectacles could show all who watched, the vulnerability of those who sat on top of the social order.

(Long before: Alexander the Great, king of Macedon, was encouraged by his friends to participate in the Olympic Games. They were impressed by his great speed, but he discerned the risk of exposing his mystique and competing against ‘the common man’; and, therefore, is reputed to have said "he would do so only if he might have kings to run with him." Perhaps this spirit is what motivated the Roman legislation.)

Additionally, there were frequent efforts to ban certain components of "the games" in order to prevent the populace from being "corrupted", and the values believed responsible for upholding the greatness of Rome from being undermined.

The theater was a common target of such legislation. In 151 BC a large stone theater nearing completion was, in fact, ordered demolished by the Senate which heeded P. Scipio Nasica’s warning that it was "useless and injurious to public morals."

The content of many of the performances was deemed immoral; lewd; disrespectful; and valueless; there were frequent moments of conflict and discord as factions supporting rival performers clashed; or "rabble-rousers" and protesters descended on the theater to push their political agendas; or as themes or performances seemed to be critical of the ruling class. At various times in Roman history, certain kinds of performances were outlawed, and performers were even banished or executed.

In spite of these dynamics of resistance, however, the Roman games only grew stronger as time went on. In democratic Republican times, the public figures who opposed or limited them lost valuable political capital, and most often ended up sabotaging their political careers, exposing themselves to defeat in the next election; in Imperial times, the Emperors recognized the crucial social value of the games as outlets for the masses to let off their steam without threatening the system; as distractions of critical importance, and allies in their own survival.

To truly understand the games--before continuing on to the always fascinating, always shocking details of the spectacles--it is necessary to take a closer look at the social history of Rome. It is in this history--in the tense and unresolved relations between the classes--that the true meaning, and perhaps the greatest damage of the games, will be found…

Ultimately, Rome fell because its rich and poor could never bridge the gap between them; and in the tragedy of its demise, the Games played a major role.

Rome gave in to a system designed to placate everyone, without solving anything. Shallow answers were chosen over deep ones, because deep ones were no longer possible without terrible pain; and it is always easier to send one’s pain into the future--to let others suffer for what one has left undone. In a nutshell, the solution to Rome’s social crisis was one in which the rich would continue to dominate, and the poor, in between social bright spots, would continue to lose their land, and struggle to find employment. No adequate plans or social measures would be put into place to prevent poverty from existing or expanding; rather, the social volatility of poverty would be neutralized by the safety net of the dole--free grain, or "bread"--to be distributed, at state expense, to the poor; and by the presentation of ever more spectacular games and entertainments, meant to distract those who might otherwise have rebelled, to channel anger into the passion of spectatorship, and to hide the wounds of injustice which cut into the lives of the poor beneath the wounds of gladiators, dying for them, as they were dying for the rich.

The Colosseum provided vastly improved settings for the enjoyment of the spectacles, its magnificence provided an illusion of opulence, a kind of part-time wealth, for the poor, the out-of-work, the oppressed, the overcrowded, the miserable and the powerless.

To maintain this system, wealth from outside of the system needed to be brought in, which implied conquest, followed by occupation, tribute, and taxation. But to seize and control this external wealth, which was used to buy off the revolution that the system would otherwise have created through its unremedied faults, also required huge expenses--for the maintenance of gigantic armies, positioned throughout the entire ancient world, was no simple matter.

Tax increases were the logical, if deadly response: tax increases to pay for the grain, the games, the armies.

But of course these taxes only broke the back of the remaining productive sectors, creating even more proletarians, who ended up in Rome, dependent upon free bread, and the pacifying mechanism of the games.

And thus the economic vibrancy and human strength of the Empire began to rot away, as men who might have been virile farmers and citizen-soldiers were disowned, then made too weak to be revolutionaries by a system seemingly designed to enmesh and emasculate them.

Ultimatly the rich did not sufficiently respect or accommodate the poor. An unbridgeable social gap made democracy unworkable. The dictatorship of the Emperors was the result. Although democracy was destroyed, social justice was not implemented. The Emperors did not bridge the gap between the classes; instead, they played the part of the champions of the people while they left the gap intact; they became overseers of a compromise that deterred class war, placating the poor while preserving the benefits of inequality; they bought social peace with free bread and games, paying for it with wealth torn from other lands. A huge and convoluted process, in place of a far simpler, fairer and more efficient one, was thus set into motion to try to preserve the Empire: a system of war, taxation and pillage, avoidance and placation, which was doomed by its own internal clock of moral, spiritual, and material decline to fall victim to the very things it was running from.

Does it take foresight, or merely courage to read the writing on the wall?

The Roman satirist Juvenal wrote, in sad disgust, in the early Imperial era: "The people who have conquered the world now have only two interests--bread and circuses."

Hmmmmm?

What this country needs is either a good 5¢ cigar or the reincarnation of an Illinois “rail-splitter” willing to tell the American people “what up” – “what really up.”

We have for so long now been willing to be entertained rather than informed, that we more or less accept majority opinion, perpetually shaped by ratings obsessed media, at face value.

After 12 months of an endless primary campaign barrage, for instance, most of us believe that a candidate’s preacher – Democrat or Republican – should be a significant factor in how we vote.

We care more about who’s going to be eliminated from this week’s American Idol than the deteriorating quality of our healthcare system. Alternative energy discussion takes a bleacher’s seat to the latest foibles of Lindsay Lohan or Britney Spears.

...and then we wonder why gas is four bucks a gallon!

(soon to be five, then six, then seven...)

We care as much as we always have – we just care about the wrong things: entertainment, as opposed to informed choices; trivia vs. hardcore ideological debate.

It’s Sunday afternoon at the Coliseum folks, and all good fun, but the hordes are crossing the Alps and headed for modern day Rome – better educated, harder working, and willing to sacrifice today for a better tomorrow.

Can it be any wonder that an estimated 1% of America’s wealth migrates into foreign hands every year?

We, as a people, are overweight, poorly educated, overindulged, and imbued with such a sense of self importance on a geopolitical scale, that our allies are dropping like flies.

“Yes we can?” Well, if so, then the “we” is the critical element, not the leader that will be chosen in November.

Let’s get off the couch and shape up – physically, intellectually, and institutionally – and begin to make some informed choices about our future.

Lincoln didn’t say it, but might have agreed, that the worst part about being fooled is fooling yourself, and as a nation, we’ve been doing a pretty good job of that for a long time now.